Writing a struct deserializer with Zig metaprogramming

I recently designed a simple struct deserializer for reading game asset data in Reckless Drivin’. This code was straightforward to write, and has considerably sped up my progress in rewriting the game. Because the code is simple and has helped me so much, I thought it would make a good Zig metaprogramming example to share.

In this post I explain both the layout of game data in Reckless Drivin’, and how the Zig struct deserializer works. If you are only interested in the Zig metaprogramming and deserialization part, feel free to skip ahead.

Data in Reckless Drivin

I have written about parts of this in detail before, so I will only cover the data layout at a high level. See my other writing about Reckless Drivin’ if you are interested in more information on the resource fork, LZRW compression, or the overall project.

The resource fork

Reckless Drivin’ is a Macintosh game that stores assets (sprites, textures,

sounds, fonts, level data, etc.) inside the resource fork of the application.

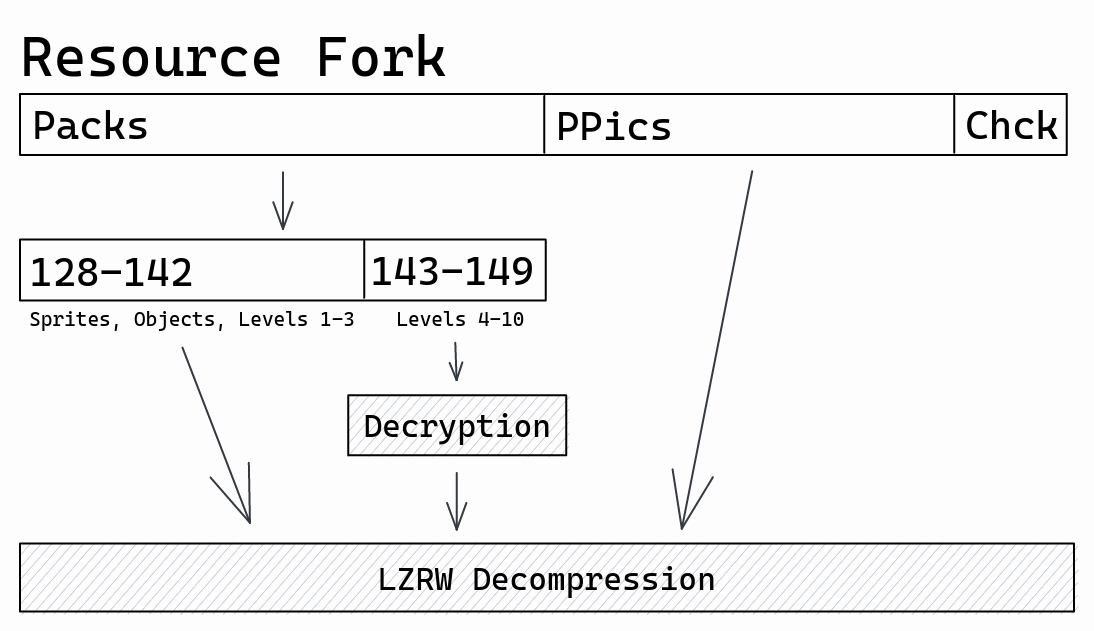

There are 3 types of resources, Packs, PPics, and Chck.

-

Packresources store indexed entries in an array of bytes. For examplePack 129stores all of the game sprites which can be looked up by entry ID. There are 22 differentPackresources. -

PPicresources store compressed PICT (Apple QuickDraw) images used for the menu and loading screens. There are 10PPicimages in the game. -

The

Chckresource is a 32 bit integer used to verify valid decryption of level data.

All Pack and PPic data is stored LZRW

compressed.

Levels 4 through 10 were only available to players who purchased the full game

and must be decrypted with a registration

code

before decompression. I have included a diagram showing the structure of the

resource fork below.

In my implementation I use Zig’s @embedFile() builtin function to insert the

full resource fork data as an array of bytes directly in the executable.

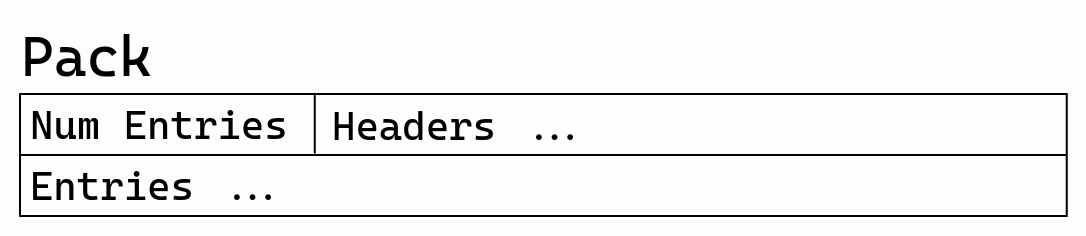

Packs

Most of the game assets are stored in Pack resources. Each Pack stores data

in slightly different formats, but the overall structure is the same. Each

Pack is prefixed with a series of eight-byte headers that contain entry IDs

and indexes into the Pack.

const Header = struct {

entry: i16,

pad: i16,

offset: u32,

}

The first header’s entry field stores the number of entries in the Pack. The

remaining headers can be indexed as an array1 to find a desired entry. The offset

points to the position in the byte stream where that entry begins.

The entries are usually struct data (which is why I need to deserialize the entries), but other entries are simple arrays of bytes used for textures and other data.

Endianness

In the original C source code of Reckless Drivin’, deserialization is done with

direct pointer casts. For example, the function GetSortedPackEntry returns a

char pointer to an entry in a Pack which is cast to a tLevelData type.

tLevelData *levelData = GetSortedPackEntry(kPackLevel1 + gLevelID, 1, nil);

Unfortunately Reckless Drivin’ was written for the PowerPC architecture which is big endian, which means all of the data in the resource fork is stored big endian. The architectures I am targeting are little endian, so a simple cast like this will not work for deserializing the bytes.2

When I was first reimplementing the game in C, I ended up writing code that read

the values into a struct one at a time. I would then also need to remember to

flip the endianness of each value. This was a messy and error-prone process, and

resulted in a lot of very similar code duplicated everywhere. Here is a

truncated example that reads a PixMap struct in C:

static PixMap PM_read(char **bytes) {

PixMap pix_map;

pix_map.base_addr = int_read(bytes);

pix_map.row_bytes = short_read(bytes);

pix_map.bounds = rect_read(bytes);

pix_map.pm_version = short_read(bytes);

pix_map.pack_type = short_read(bytes);

...

Here I had to ensure I used the correct *_read function for each data type,

and to also not forget to flip the bytes when done.

Thanks to Zig’s compile-time metaprogramming, designing a deserializer that

would flip the bytes to the correct endianness was easy. To read an ObjectType

struct in Zig with my deserializer all I need is the following code:

const obtype = try packs.getEntry(ObjectType, .object_type, entry);

This will generate code specific to reading ObjectType data, including

endianness flipping. I’m very pleased with how easy this is compared to my

original C code, and I also think it provides good context to highlight some of

Zig’s features. Let’s dive into how this works.

Writing a struct deserializer with Zig

To keep things simple3 I have extracted my deserializer from my source code and removed anything unnecessary.

If you skipped the section giving context on Reckless Drivin’, you will need to know that the data is stored big endian because the original game was designed for PowerPC on Mac OS 9.

I will walk through the code, starting from the main function and build up the

deserializer piece by piece. Because Zig is a new and unfinished language, I

will also take some time to point out things that might be unfamiliar, but I

also won’t be explaining everything to keep this from getting too long.

I have also included the full code below if you want to view everything together.

View the full deserializer code

const std = @import("std");

const bigToNative = std.mem.bigToNative;

pub const Reader = struct {

bytes: []const u8,

index: usize,

pub fn init(bytes: []const u8) Reader {

return .{ .bytes = bytes, .index = 0 };

}

fn readInt(self: *Reader, comptime T: type) !T {

const size = @sizeOf(T);

if (self.index + size > self.bytes.len) return error.EndOfStream;

const slice = self.bytes[self.index .. self.index + size];

const value = @ptrCast(*align(1) const T, slice).*;

self.index += size;

return bigToNative(T, value);

}

fn readFloat(self: *Reader) !f32 {

const size = @sizeOf(f32);

if (self.index + size > self.bytes.len) return error.EndOfStream;

const slice = self.bytes[self.index .. self.index + size];

const value = @ptrCast(*align(1) const u32, slice).*;

self.index += size;

return @bitCast(f32, bigToNative(u32, value));

}

fn readStruct(self: *Reader, comptime T: type) !T {

const fields = std.meta.fields(T);

var item: T = undefined;

inline for (fields) |field| {

@field(item, field.name) = try self.read(field.field_type);

}

return item;

}

pub fn read(self: *Reader, comptime T: type) !T {

return switch (@typeInfo(T)) {

.Int => try self.readInt(T),

.Float => try self.readFloat(),

.Array => |array| {

var arr: [array.len]array.child = undefined;

var index: usize = 0;

while (index < array.len) : (index += 1) {

arr[index] = try self.read(array.child);

}

return arr;

},

.Struct => try self.readStruct(T),

else => @compileError("unsupported type"),

};

}

};

const Point = struct { x: i32, y: i32 };

const Data = struct {

pi: f32,

points: [2]Point,

pad: u32,

num: u64,

byte: u8,

};

pub fn main() !void {

// Big endian serialized Data struct in bytes

const bytes = [_]u8{

0x40, 0x49, 0x0f, 0xdb, // pi

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, // points[0].x

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, // points[0].y

0x00, 0x00, 0x02, 0x12, // points[1].x

0x00, 0x00, 0x01, 0xff, // points[1].y

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, // padding

0x12, 0x34, 0x56, 0x78, // num

0x90, 0xab, 0xcd, 0xef,

0xff, // byte

};

var reader = Reader.init(&bytes);

const parsed = try reader.read(Data);

std.debug.print("{}\n", .{parsed});

}

While there are many structs in Reckless Drivin’ that could be used as an example, I have chosen to make a smaller struct to keep things more focused (some of the structs in Reckless Drivin’ have over 20 members). Here is what we will be working with:

const std = @import("std");

const bigToNative = std.mem.bigToNative;

const Point = struct { x: i32, y: i32 };

const Data = struct {

pi: f32,

points: [2]Point,

pad: u32,

num: u64,

byte: u8,

};

pub fn main() !void {

// Big endian serialized Data struct in bytes

const bytes = [_]u8{

0x40, 0x49, 0x0f, 0xdb, // pi

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, // points[0].x

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, // points[0].y

0x00, 0x00, 0x02, 0x12, // points[1].x

0x00, 0x00, 0x01, 0xff, // points[1].y

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, // padding

0x12, 0x34, 0x56, 0x78, // num

0x90, 0xab, 0xcd, 0xef,

0xff, // byte

};

// TODO: deserialize the bytes

}

This code declares two struct types, Point and Data. A Point is two

unsigned 32-bit integers. Data contains a variety of numbers, and an array of

two Point values.

Notice that the Data struct has been explicitly padded with pad: u32. This

is not necessary, but the data in Reckless Drivin’ is manually padded so I am

doing that here for consistency.

In the main function I declare a constant array of u8 bytes to be deserialized

into a Data struct value.

I also import an reference to the standard library, and the bigToNative function used for byte swapping.

Creating the deserializer struct

Zig structs can contain namespaced functions. I think this makes the

deserializer code more organized so I will create a Reader struct to hold all

of the deserializer logic.

const Reader = struct {

bytes: []const u8,

index: usize,

pub fn init(bytes: []const u8) Reader {

return .{ .bytes = bytes, .index = 0 };

}

pub fn read(self: *Reader, comptime T: type) !T {

// TODO

}

};

This Reader struct contains two fields, a slice of bytes and an index tracking

the current position in the slice. I have included an init function to more

easily construct instances of the Reader struct with the fields properly

initialized, but this isn’t necessary. I also have the stub of the read

function which we will get to later.

With this done we can finish the main function.

const Data = struct {

// omitted

};

pub fn main() !void {

const bytes = [_]u8{

// omitted

};

var reader = Reader.init(&bytes);

const parsed = try reader.read(Data);

std.debug.print("{}\n", .{parsed});

}

Here I create a reader, parse the bytes with reader.read(Data) and print out

the parsed struct.

Before moving on, there is one interesting thing I would like to point out. In

Zig with a struct variable x of type T, the x.f() syntax is just syntactic

sugar for T.f(&x), so we could have written Reader.read(&reader, Data) instead of

reader.read(Data) if we had wanted to.

At this point the main function is complete and everything else will be added

to the Reader struct.

Comptime

You may have noticed that the type Data was passed to the read function, and

that the type of the second parameter T is type. Zig types are first-class

values at compile time. With that in mind, let’s now implement the read function.

pub fn read(self: *Reader, comptime T: type) !T {

return switch (@typeInfo(T)) {

.Int => try self.readInt(T),

.Float => try self.readFloat(T),

.Array => |array| {

// TODO

},

.Struct => try self.readStruct(T),

else => @compileError("unsupported type"),

};

}

This function will be partially evaluated at compile time due to the comptime

labeled parameter T. At comptime the @typeInfo() builtin function allows

type reflection. Here we use a switch statement to match int, float, array, and

struct types. Attempting to deserialize any other type will result in a compile

error. We will fill in the array parsing logic later.

For each allowed type, an additional helper function is called to handle reading

that specific type (e.g. readInt). The result of that helper function is

returned.

One thing to point out here is that Zig’s compile-time language is Zig! Unlike some languages where there is a separate macro or preprocessor language, Zig metaprogramming does not require learning a new syntax. Reflecting on a type uses a simple function call and switch statement.

Handling errors in Zig

Before moving on, let’s also talk about Zig error handling.

Any Zig function that has a ! in the return value indicates an error union.

That means the function could return an error, or a value of the specified type.

The compiler ensures that all errors are handled.

The try keyword before a function call tells Zig to return an error, or

continue with the function if there was no error.

Throughout the Reader code we will use the try keyword to pass errors up to the

caller. The only error that any Reader function can return is

error.EndOfStream. It doesn’t make sense to handle this error in any of the

Reader functions because it doesn’t know how the user wants to handle it.

In our main function we also use try, which means if the reader went out of

bounds main would exit early with an error. We could easily handle the error

in main if we wanted to though.

// to handle the error, try is replaced with a catch operator and block

const parsed = reader.read(Data) catch {

std.debug.print("error: not enough bytes to unpack!\n", .{});

return;

};

Had there been more types of errors returned from read we could have done a

switch on the type of error to handle each error type differently.

Zig errors are nothing more than a modification to the return type, making it a union type. The compiler then enforces that errors are handled, or ignored when the programmer chooses to assert that things are safe.

With that out of the way, let’s finally start parsing some bytes!

Reading integers

We will start with the readInt function.

fn readInt(self: *Reader, comptime T: type) !T {

const size = @sizeOf(T);

if (self.index + size > self.bytes.len) return error.EndOfStream;

const slice = self.bytes[self.index .. self.index + size];

const value = @ptrCast(*align(1) const T, slice).*;

self.index += size;

return bigToNative(T, value);

}

Here we use the @sizeOf() builtin function to get the size of the integer type

in bytes. Then we do some error checking: if reading that many bytes would move

past the end of the stream, an EndOfStream error is returned.

Otherwise a slice of size bytes is created. The @ptrCast() casts the slice

to the desired integer pointer type, here a pointer to a constant unaligned T,

followed by .* to dereference the pointer. This is similar to the C code T

value = *((T *) slice). Zig requires us to specify alignment of

pointers,4 and casts are done via a builtin function rather than

special syntax.

The index is incremented so the next read starts in the correct position, and

the value is byte swapped with bigToNative and returned.

As I mentioned earlier these comptime functions will be specialized. If we ran

reader.readInt(i32) we could imagine the following function to be generated.

fn readInt_i32(self: *Reader) !i32 {

if (self.index + 4 > self.bytes.len) return error.EndOfStream;

const slice = self.bytes[self.index .. self.index + 4];

const value = @ptrCast(*align(1) const i32, slice).*;

self.index += 4;

return bigToNative(i32, value);

}

This is how generic functions work in Zig; no special syntax or macros, just compile-time known type parameters. A specialized function will be created for each type of integer to be parsed.

Reading floats

Reading floats is very similar to reading integers. In Reckless Drivin’ no

64-bit floats are ever used in game assets, so I haven’t bothered to make this

function work for anything other than f32.

fn readFloat(self: *Reader) !f32 {

const size = @sizeOf(f32);

if (self.index + size > self.bytes.len) return error.EndOfStream;

const slice = self.bytes[self.index .. self.index + size];

const value = @ptrCast(*align(1) const u32, slice).*;

self.index += size;

return @bitCast(f32, bigToNative(u32, value));

}

The bigToNative standard library function only works on integer types. So to

read and byte swap a floating point value we read it as a u32, then

@bitCast() the value to a float when returning it.

Reading structs

Struct deserialization is my favorite part of the Reader, and is what makes it

such a powerful tool in my Reckless Drivin’ rewrite. And in my opinion it is

amazingly simple. Let’s take a look at the code:

fn readStruct(self: *Reader, comptime T: type) !T {

const fields = std.meta.fields(T);

var item: T = undefined;

inline for (fields) |field| {

@field(item, field.name) = try self.read(field.field_type);

}

return item;

}

Here fields uses a metaprogramming function from the standard library that

returns a slice of all of the fields of a given struct. Each element in the

slice contains data about the name, the type, and more about that field.

Then we declare item; an uninitialized (undefined) value of the struct type.

An inline for loop is a special loop that will be unrolled at compile time. We

iterate over the fields of the struct. For each field the @field() builtin

function is used to access the . operator. For example, if a struct field was

named x, then @field(item, field.name) is the same as item.x. Then that

field is assigned with the result of reading a value of the field type.

As a concrete example, this would be specialized to something like the following

for our Data struct.

fn readStruct_Data(self: *Reader) !Data {

var item: Data = undefined;

item.pi = try self.read(f32);

item.points = try self.read([2]Point);

item.pad = try self.read(u32);

item.num = try self.read(u64);

item.byte = try self.read(u8);

return item;

}

Code like this is where the power of Zig comptime really clicked for me. With a simple for loop and a few function calls, it is trivial to reflect on the layout of a struct and generate code specialized to that type. I love that this powerful tool uses the same syntax as regular Zig code.

Reading arrays

The final step is to include the code for parsing arrays. I chose to include

this directly in the read function, but it could just as easily have been

written as a separate function.

pub fn read(self: *Reader, comptime T: type) !T {

return switch (@typeInfo(T)) {

.Int => try self.readInt(T),

.Float => try self.readFloat(),

.Array => |array| {

// this is the new code

var arr: [array.len]array.child = undefined;

var index: usize = 0;

while (index < array.len) : (index += 1) {

arr[index] = try self.read(array.child);

}

return arr;

},

.Struct => try self.readStruct(T),

else => @compileError("unsupported type"),

};

}

Here |array| captures data about the array. We allocate a new array of the

specified length and child type. This works because this information is known at

compile time! Then we iterate for the length of the array, setting each index to

the result of reading a value of the child type with self.read. The array is

then returned.

Running the code

At just 62 lines, that’s all of the code for the deserializer! You can jump back if you want to see all of the code together.

When executed with zig run main.zig it outputs the following (I reformatted

the output to be on multiple lines rather than one):

$ zig run main.zig

Data{

.pi = 3.14159274e+00,

.points = {

Point{ .x = 0, .y = 0 },

Point{ .x = 530, .y = 511 }

},

.pad = 0,

.num = 1311768467294899695,

.byte = 255

}

This deserializer is designed specifically for my needs in Reckless Drivin’. It assumes the input bytes are big endian, and it only supports the types I use. The implementation was straightforward, and I think it clearly shows how Zig’s metaprogramming model can make small utilities like this really easy and natural to write. This could easily be adapted to read the bytes from a file rather than from memory for example.

But how does it perform?

I brought the code over to Compiler Explorer to see the disassembly. Here’s a link if you want to experiment with the full code and disassembly.

Note that I removed the main function and call to std.debug.print in favor

of an exported function. This removes a lot of extra code so the only thing

shown in the disassembly is the code we actually care about. I also added a

statement to sum all of the values in the struct and return the sum to ensure

the compiler didn’t discard any values.

When first writing this deserializer I was worried that there might be code

bloat and a performance penalty from generating so many specialized reader

functions. And indeed in an unoptimized debug build (Remove -OReleaseFast from

the Compiler options), the various reader functions for different types are

still present.

But Compiler Explorer shows that in release builds LLVM reduces things into very

optimized instructions. The link above (a ReleaseFast build) is only 46 lines of

disassembly and no function calls. The ReleaseSafe build is similar, but also

includes safety checks. Here is an excerpt of the disassembly showing the mov*

instructions that read the seven values we use from the Data struct.

movbe eax, dword ptr [rdi]

mov esi, dword ptr [rdi + 4]

mov ecx, dword ptr [rdi + 8]

shl rsi, 32

or rsi, rcx

bswap rsi

mov edx, dword ptr [rdi + 12]

mov ecx, dword ptr [rdi + 16]

shl rdx, 32

or rdx, rcx

bswap rdx

movbe r8, qword ptr [rdi + 24]

movzx ecx, byte ptr [rdi + 32]

In this case it generated a mixture of mov and bswap instructions, and even

a movbe to read and byte swap all at once for the 64-bit value.

Final thoughts

So that’s my take on struct deserialization in Zig!

I really enjoy Zig’s approach to metaprogramming. While not as powerful as something like Racket, Zig still offers great tools for compile time programming. And even though comptime is more limited than some macro systems, I think the consistent and simple5 route that Zig takes is worth it.

I hope this has been an informative read! Please let me know if anything is unclear, or if you find any errors.

-

In reality it isn’t that simple. Some of the packs store sparsely packed data. A pack could contain 100 entries, but the entry IDs could range from 128 to 1009 which makes it impossible to index as a simple array. Because the entry IDs are sorted, entries in these packs are found by using a binary search.↩︎︎

-

This is a good thing though, because it has forced me to implement the code in a manner that will work regardless of the endianness!↩︎︎

-

In Reckless Drivin’ the

packs.getEntryfunction uses aReaderinternally, but there are quite a few layers between getting a pack entry and using theReaderI am showing here.↩︎︎ -

Here we use

*align(1) const Tto specify that the pointer is aligned to bytes, or unaligned. SayTwas an i32 which has an alignment of 4. Without specifyingalign(1)in the pointer type, Zig would refuse to pointer cast because casts are not allowed to increase pointer alignment.This does mean that Zig will attempt to cast (load) memory across byte boundaries if the input data is not aligned. In Reckless Drivin’ I have specified the alignment of my input bytes to avoid this, but have not included this here for simplicity.

But most modern architectures support unaligned loads, so this really shouldn’t be a huge deal anyway.↩︎︎

-

Comptime programming is done with the same syntax as runtime code.↩︎︎