Unpacking LZRW-compressed game assets from resource forks

Reckless Drivin’ is a shareware Macintosh game released by Jonas Echterhoff in 2000. Jonas released the source code on GitHub in 2019, but the game is difficult to compile due to the dependency on deprecated Apple system calls and the CodeWarrior project structure. I have been working on Open Reckless Drivin’ off and on over the last couple years to modernize the code and release the game for all platforms, and my previous post about Open Reckless Drivin’ explains more about my goals with this project. This post shares interesting things I learned while unpacking the game assets from the binary file Jonas released.

While I used an Apple PowerBook G4 to play Reckless Drivin’ when I was younger, I never used a PowerPC Mac at an age when I could understand things like QuickDraw, Resource Forks, and LZRW compression. So this project has been a really interesting learning experience to understand what is now part of computing history. The project is far from finished, and I have had parts of this post written up for over a year now, so I figured I might as well finally share it in hopes that others will also find it interesting.

Learning about resource and data forks

After cleaning up the source code of Reckless

Drivin’, my first goal was to read

the contents of the file called Data. This file includes the images, sprites,

textures, level data, sounds, and other game assets. The

commit

that introduced the file is titled “resource fork”. The project’s readme says:

To be able to upload this to git… the resource forks of the rsrc files have been moved to the data fork.

Until this point I hadn’t ever heard of resource or data forks, so I turned to Wikipedia and archived Macintosh articles to learn more.

On some file systems, like Apple’s HFS+ that Reckless Drivin’ was developed on, files can contain forks). Forks are sets of data associated with the file in the file system. Although there was support for an arbitrary number of forks, most Macintosh software only used the data and resource forks. On PowerPC machines the executable was stored in the data fork, and the resource fork stored structured data associated with the file like icons, images, and sounds. These resource forks are essentially databases stored alongside an executable.

Each resource stored in the resource fork has a four-byte type identifier,

usually a four-character label, and a two-byte ID number. An example resource

type would be PICT for picture. This

table lists

some of the most common types of data stored in resource forks.

From C source code, a resource can be accessed with the following call, passing the type1 and the id:

Handle picture = GetResource('PICT', 1000);

This returns a handle pointing to memory where the resource was stored. Many tools like git only read information from the data fork, which is why Jonas moved all the data from the resource fork to the data fork before committing in git.

Extracting the resources with DeRez

Once I knew the resource data was stored in Data, I needed to find a way to

read the file and see what it contained. Some searching led me to a Mac tool

called DeRez used for decompiling

resources. It happens to be bundled with Xcode command line tools, so I borrowed

a friend’s Macbook, installed DeRez, and processed Data with it. The output

format resembles xxd, with the hex bytes on the left and an ascii representation

on the right. Each resource is listed in a data block surrounded by {}

characters. Here’s a small2 portion of the decompiled output file.

$ derez -useDF Data > unpacked_data

$ head unpacked_data

data 'Pack' (128, "Object Definitions") {

$"0000 2C78 0000 0000 A010 009E 0000 0001" /* ..,x.......... */

$"0280 0102 04F8 0081 0102 0538 0022 2282" /* ........8."" */

$"0204 7800 8302 01B8 0084 0201 F800 8501" /* ..x........ */

$"0106 3844 4400 8602 0578 0087 0202 B800" /* ..8DD...x.... */

$"8802 02F8 0089 0101 0788 8838 008A 0206" /* ......8... */

$"7800 8B02 03B8 008C 0203 F800 8D01 0110" /* x.......... */

$"1108 3800 8E02 0778 008F 0204 B800 9002" /* ..8...x..... */

$"00F8 0091 2122 0100 0938 0092 0200 7800" /* ..!"...8...x. */

$"9302 00B8 0094 0200 F800 4244 9501 000A" /* ......BD... */

This resource is of type Pack and has an ID of 128. Other resource types in

the file include PPic and Chck, none of which are standard resource

types. Some

of the resources are helpfully labeled with a description string. Most of the

resources are Packs including:

- Object Definitions

- Road Characteristics

- Level Data

- Sounds

Unpacking Data verified that all of the game assets were preserved, but I

still needed a way to read the file in code. I couldn’t find any information on

the resource file format, so I decided to write a small Python

script

to store the unpacked data in a more compact format of my choosing. Each

resource is represented in memory by the following struct, which stores the type

identifier, the ID number, and an array of data with its associated length.

struct Resource {

char type[8];

uint32_t id;

uint32_t length;

char *data;

};

Note that the integer sizes in this struct are larger than needed. I could repack the data to align with the exact integer sizes used for the type and ID, but that doesn’t really matter.

The output of the script took the bytes from the DeRez unpacked Data file, and

placed them end to end with the headers from the Resource struct. This made it

trivial to write a C program to iterate over the resources stored in the data

file to find any resource given a type and ID. The next step was to find some

meaning in the bytes.

Reading the packs

Most of the game data is stored as Pack resources. These packs are read into

memory by the uint32_t LoadPack(int num) function.

uint32_t LoadPack(int num) {

uint32_t check = 0;

if (!packs[num]) {

packs[num] = GetResource("Pack", num + 128);

if (packs[num]) {

if (num >= PACK_ENCRYPTED) {

check = CryptData((uint32_t *)*packs[num], GetHandleSize(packs[num]));

}

LZRWDecodeHandle(&packs[num]);

}

}

return check;

}

This function loads a Pack resource given an ID number and stores a handle in

a global array. This function also contains two roadblocks to interpreting the

resources:

-

Some packs are encrypted, as indicated by the call to

CryptData()when the pack number is above a certain value. This is because levels 4 through 10 were restricted to registered players. -

Each pack is compressed by the LZRW algorithm which is decompressed by a call

to

LZRWDecodeHandle().

Because decompression is needed for all Pack and PPic resources, that is

what I will focus on for the remainder of this post. I will describe the process

of decrypting the level data in a later

post.

LZRW decompression

LZRW (Lempel-Ziv Ross Williams) is a family of compression algorithms created by Ross Williams that are focused on speed rather than high compression. Ross created seven variants of the algorithm before fears related to software patents caused him to leave the world of data compression behind. In 1997 he released all of his algorithms on his “compression crypt” website. Ross’ website is not always available online, so here’s an archived link to his homepage where the seven compression algorithms are located. A compression benchmarking repo on GitHub also contains the source code for most of the variants, with an additional header file to create a common interface for the different source files.

Unfortunately the Reckless Drivin’ source code shared by Jonas is missing the file for LZRW decompression. Ross Williams’ website includes all the source code for the algorithms, but there are seven variations, and Reckless Drivin’s code doesn’t mention which of the seven was used.

The variants all follow a similar interface, so I created a test

program

to load a pack and decompress it with the chosen algorithm. When compiling this

program I enabled the address sanitizer in gcc with -fsanitize=address. With

no other indication of success, I decided that If the pack would decompress

without memory issues, then the LZRW variant worked.

At this point I thought this task would be simple: Decompress all the packs with each variant until one variant decompressed without memory issues. I soon found a problem because more than one of the variants succeeded without issue. Both lzrw3 and lzrw3-a would successfully decompress all of the files with no memory issues. Some of the other algorithms like lzrw1 would decompress some of the resource packs, but would fail with out-of-bounds memory accesses with other packs.

Because multiple variants decompressed successfully, I would now need to look at

the bytes in the decompressed resource packs to determine if the data was

decoded properly. Because the Pack resources are cast directly to various

structs in Reckless Drivin’, it would be very difficult to find any obvious

patterns in the data. So I turned to the PPic resources instead.

QuickDraw graphics

By looking at the function calls surrounding the uses of the PPic resources in

Reckless Drivin’, I determined that the data was stored in the

QuickDraw format.3 These images

are used for the loading screen, menus, and credits screens in Reckless Drivin’.

QuickDraw is an Apple graphics library documented in Inside Macintosh: Imaging

With

QuickDraw

which is helpfully archived on Apple’s developer website. This 822 page PDF file

documents both the API for using QuickDraw, and the binary file format for the

images when saved to disk. QuickDraw files contain a series of 2-byte opcodes

that construct the image through lines, rectangles, polygons and other

predefined shapes. Bitmap image data can also be drawn with QuickDraw. The

PPic images were created with QuickDraw extended version 2, and the Imaging

With QuickDraw PDF describes the opcodes starting on page 731. Some of the

opcodes include

-

0000: No Operation -

0007: Set the pen size -

0020: Draw a line

The QuickDraw format also specifies certain bytes that are stored in the header of the image:

In a picture created in extended version 2 or version 2 format, the first opcode is the 2-byte VersionOp opcode: $0011. This is followed by the 2-byte Version opcode: $02FF

With this information I thought I could look at the decompressed PPic files

and look for header bytes like 0011 and 02FF to confirm that the

decompression was successful. The QuickDraw PDF also contains a decompiled

QuickDraw image on page 749 which was a great reference for comparing against

the binary files.

data 'PICT' (128) {

$"0078" /* picture size; don't use this value for picture size */

$"0000 0000 006C 00A8" /* bounding rectangle of picture at 72 dpi */

$"0011" /* VersionOp opcode; always $0011 for extended version 2 */

$"02FF" /* Version opcode; always $02FF for extended version 2 */

$"0C00" /* HeaderOp opcode; always $0C00 for extended version 2 */

/* next 24 bytes contain header information */

$"FFFE" /* version; always -2 for extended version 2 */

$"0000" /* reserved */

$"0048 0000" /* best horizontal resolution: 72 dpi */

$"0048 0000" /* best vertical resolution: 72 dpi */

$"0002 0002 006E 00AA" /* optimal source rectangle for 72 dpi horizontal and 72 dpi vertical resolutions */

$"0000" /* reserved */

Here is the header of PPic 1000 after decompression with lzrw3.

$ xxd ppic-1000 | head -n 2

00000000: 0000 0000 7f10 0000 0000 01e0 0280 0011 ................

00000010: 0c31 3233 00ff fe00 0248 3132 3334 3536 .123.....H123456

Comparing the two there are many similarities, and I began to be excited, but

closer inspection showed that there wasn’t a perfect match between the expected

header information, and what PPic 1000 contained. The 0011 and fffe

bytes are in the file, but aren’t in the expected locations or alignments.

Another confusion is that the uncompressed PPic resources also contained

the 0011 and fffe byte sequences, and were in some ways more aligned with

the specification!

data 'PPic' (1000) {

$"0005 7F10 0000 0000 0000 7F10 0000 0000"

$"01E0 0280 0011 02FF 0C00 7400 FFFE 0002"

The version opcodes are in the uncompressed data, but not in the correct locations. This makes sense, because the uncompressed data needs to exist somewhere in a compressed file, and this compression algorithm happened to keep these bytes intact. But the fact that these bytes were in the uncompressed data still made me question, wondering if Jonas had decompressed the resource forks when releasing the source code.

At this point my school studies picked up and I took a break from working on this problem. Months later I had the idea to decompile the binary found on Jonas’ website to see if I was missing any steps in reading the resource data.

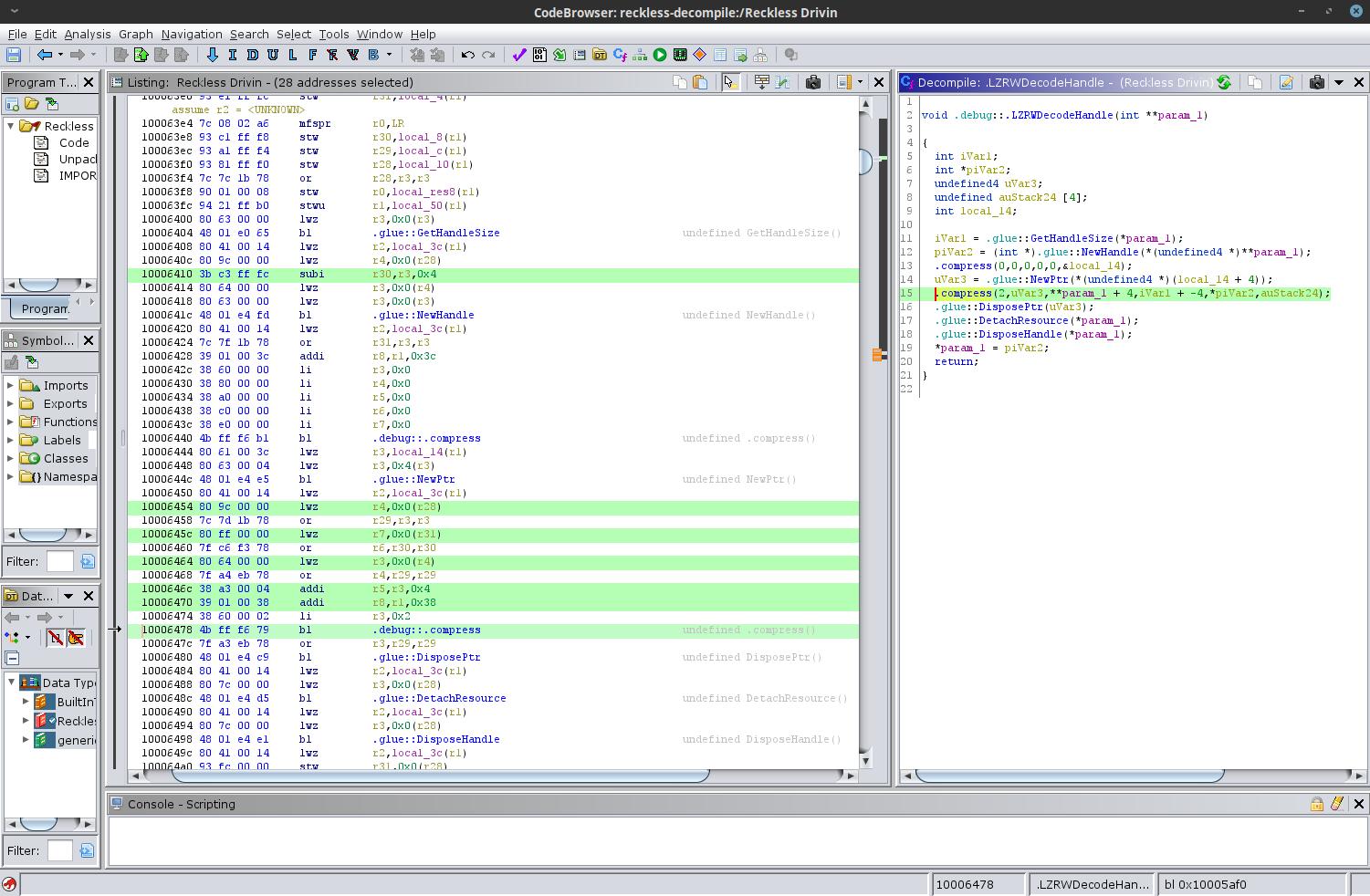

Ghidra saves the day

Ghidra, an open source reverse engineering tool

developed by the NSA is a wonderful resource for decompiling software. This

isn’t the place to explain how to use Ghidra, but if you haven’t tried it, it is

incredible. Within minutes I had the original LZRWDecodeHandle() function

decompiled in Ghidra.

The highlighted line of decompiled code is:

.compress(2,uVar3,**param_1 + 4,iVar1 + -4,*piVar2,auStack24);

This function call has the same signature as the one found in Ross Williams’

code that I used when blindly reimplementing LZRWDecodeHandle(), but with one

interesting difference that stands out. The first four bytes of the packed data

are ignored, as indicated by the +4 offset to the array, and the -4 offset to

the length of the array. I added the same offsets to my implementation and

recompiled.

lzrw3a_compress(COMPRESS_ACTION_DECOMPRESS, working_mem, **handle + 4,

handle_len - 4, dst_mem, &dst_len);

The following is PPic 1000 after decompression with the memory offset.

$ xxd ppic-1000 | head -n 2

00000000: 7f10 0000 0000 01e0 0280 0011 02ff 0c00 ................

00000010: fffe 0000 0048 0000 0048 0000 0000 0000 .....H...H......

This exactly lined up with the format described in the QuickDraw specifications,

with 0011 02ff 0c00 FFFE identifying this as an extended version 2 image, and

the remainder of the header specifying the dimensions (640x480) and other

metadata. This confirmed that the lzrw3-a algorithm was the correct variant!

I was super excited, and this breakthrough motivated some very fast paced

development on Open Reckless Drivin’ over the next few weeks.

Although at this point there still wasn’t anything besides bytes to show for all my work, it was both rewarding and motivating to have access to Reckless Drivin’s game assets in my reimplementation. This post has grown long enough, so I won’t describe the process of writing a QuickDraw interpreter until a later post. This process of unpacking the resource forks taught me a lot of interesting things about Macintosh computers, and I hope you found this interesting too!

-

The four characters of the type identifier were written inside a character literal which would be interpreted as a single 32-bit integer. This code emits a

-Wmulticharwarning in gcc, but it does work. In my reimplementation I chose to use four-character string literals instead of relying on the implementation-defined behavior of character literals.↩︎︎ -

The full output was 362,666 lines of text (27MB of data).↩︎︎

-

The conventional resource type for a QuickDraw image is

PICT. I assume thatPPicmeans Packed PICT, but unless Jonas reveals what he meant byPPicwe will never know.↩︎︎